In her short yet foundational essay titled Mr. Truman’s Degree, Elizabeth Anscombe strongly criticizes the University of Oxford’s decision to award an honorary doctorate to Harry Truman, the U.S. president who authorized the atomic bombing of Japan.

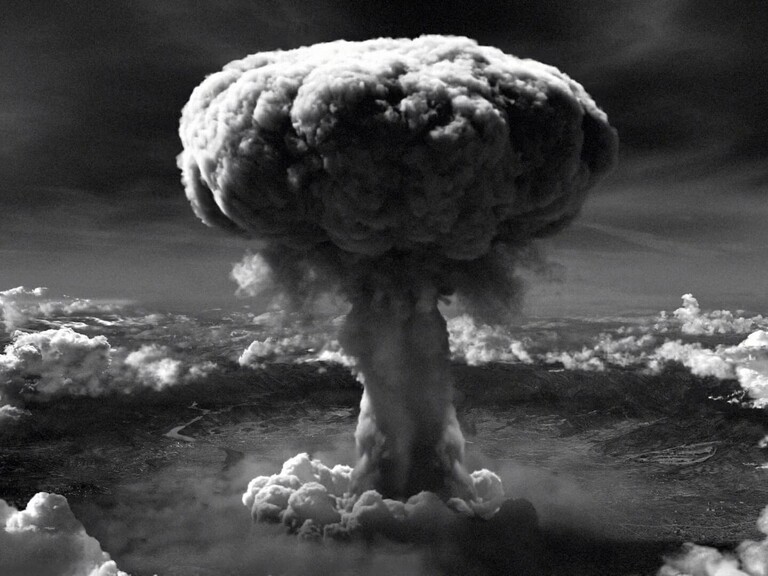

She argues that the United States destroyed the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs at a time when Japan had already twice expressed willingness to negotiate peace. However, the policy of “unconditional surrender” pursued by the Allies had blocked any possibility of compromise.

According to Anscombe, this approach was at the root of all moral disasters of the Second World War —a mindset that invalidated the distinction between combatants and non-combatants and, through the rhetoric of collective responsibility, rendered the mass killing of civilians morally permissible. Just as Nazi Germany bombed British cities indiscriminately, the Allies themselves adopted similar tactics in large-scale bombings, including the attack on Dresden.

Anscombe contends that if someone knows innocent people live in an area targeted for bombing and proceeds anyway, they are committing murder. Here, “innocent” refers to someone incapable of inflicting harm, not someone lacking political or moral responsibility. Therefore, a captured soldier or a child eating bread cannot be considered a legitimate target.

She further writes that American forces were aware in advance of Japan’s plan to attack Pearl Harbor but deliberately allowed it to happen to manipulate public opinion and justify entering the war. At the Potsdam Conference, Stalin informed the Allies that Japan had requested his mediation for peace negotiations, yet even so, the decision to drop atomic bombs was carried out, even if Japan agreed to surrender.

Anscombe emphasizes that Western military ethics in the twentieth century represented a savage regression to primitive morality, in which weapons of mass destruction and indiscriminate bombings were justified by strategic calculations. Under such logic, Truman —as a primitive and immoral figure—was not worthy of receiving an honorary degree from a university such as Oxford.

She also critiques the moral philosophy then dominant at Oxford, which prior to World War II emphasized “good intentions” and, shockingly, regarded acts such as the burning of Jews by the Nazis as morally acceptable if done in the name of duty. A form of relativism replaced this view in the 1950s, turning moral legitimacy into a matter of collective approval instead of objective reasoning.

In conclusion, Anscombe urges her readers not to attend the degree ceremony and warns that victory in war should never be mistaken for moral righteousness. Just as Hannah Arendt exposed evil in the face of Eichmann, Anscombe—writing from within Britain—reminds us that the Allies, too, committed crimes that cannot be justified by the outcome of the war.

At a time when the war still raged on, Anscombe, a philosopher whose temperament resembled that of her intellectual companion Wittgenstein, spoke with absolute clarity against the evil of war and weapons of mass destruction. It is true that many philosophers—like Bertrand Russell—supported the struggle against fascism and even saw war as a necessary evil, yet they remained opposed to violence.

Philosophers such as Simone Weil opposed not only war but violence in any of its forms. In her renowned essay The Iliad, or The Poem of Force, she described war not as a heroic endeavor but as the embodiment of brute force —an element that reduces both oppressor and oppressed into lifeless objects: “Force turns anyone who is subjected to it into a thing—in the most literal sense. It makes a corpse out of them.”

Even thinkers like Michael Walzer, Raymond Aron, Karl Popper, and William Temple —who deemed the war against fascism justified— harbored deep moral doubts about the bombing of civilian populations. And yet, look what became of moral philosophy: from Augustine and Kant, it deteriorated to a point where philosophers like Jürgen Habermas and figures like Alan Dershowitz came forth to defend Israel under flimsy pretexts.

The disciples of Leo Strauss —figures such as Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle— fractured ethics within the framework of neoconservatism and legitimized the defense of Israel regardless of its moral cost. The massacres continued, and the philosophers remained frozen in place. Poetry —contrary to Adorno’s famous claim that “there can be no poetry after Auschwitz”— persisted.

The glitz of cultural festivals buried the demonization of Palestinians, portraying them as loathsome beings worthy of eradication. Jürgen Habermas, too, fell —just as so many other intellectuals and philosophers had before him. Those who once proclaimed the highest ethical values in books and lectures now stood silent in the face of slaughter. And their disciples repeated their words so often and uncritically that their pronouncements came to be treated as sacred revelation, while dissenters were cast aside as ignorant or already dead.

Habermas, along with Nicole Deitelhoff, Rainer Forst, and Klaus Günther, issued a statement in which they condemned only “Hamas’s massacre against Israel.” But isn’t it time we begin asking of Habermas —regarding his silence on the genocide in Gaza—the very questions once posed about Heidegger and his association with Nazism?

Asef Bayat, the Iranian sociologist, wrote an open letter to Habermas, stating that his indifference to Gaza contradicts his own philosophical claims. But I believe this indifference, in fact, aligns perfectly with his internalized Zionism —the same worldview that considers the non-European as something less than fully human, or at best, a “human-like animal,” as the Israeli Minister of Defense shamelessly described Palestinians.

This worldview is not limited to Gaza; it applies equally to Sudan, Iraq, the Uyghurs, and even to Eastern migrants in Europe. So we must ask: are the philosophers who claim to speak out for Gaza sincere, or are they merely performing, hypocritically, to salvage their image?

I do not wish to discuss Edward Said’s discourse or Aimé Césaire’s words. I would like to point out that when Western philosophers display such clear double standards, it raises questions about what we can reasonably expect from ordinary people.

I am not anti-Western, nor do I oppose any human being. But the issue isn’t just Gaza. The real issue is that the Eastern human being —being the one Camus called “Algerian” in France or “Turk” in Germany— is not considered human at all.

We often fail to persuade ourselves that justice and ethics are universally applicable. But the way Syrian refugees are viewed, the competition among migrants to displace and reject one another, and the internalized hatred among the people of the East —all reflect a decaying mindset.

This mindset treats ethics as subject to majority rule, remaining silent when a German-born man commits mass murder, yet making headlines when a Syrian refugee makes a mistake.

We now live in a world where morality has become a tool to justify contradictions. Instagram filters are crushing our world, modern slogans are wrapping it, and iron walls and smart bombs are burying it. A world I, as a Middle Easterner, no longer place any trust in.

I don’t know how to chant slogans. I only ask: even if you can’t stop the killing, at least don’t look at your migrant neighbor with hatred. Thousands of shrapnel wounds lie buried beneath that mother’s dried-out chest. Even if Habermas doesn’t understand, even if Anscombe is no longer with us —Nizar Qabbani’s pomegranates still bleed red…