An Anatomy of Turkish Foreign Policy: 1995 – 2020, Issue #5: Turkey & Japan

Introduction

This study is the fifth bilateral analysis of Turkish Foreign Policy (TFP) in the research project titled: “An Anatomy of Turkish Foreign Policy.” Our goal is to quantify TFP’s evolution between 1995 and 2020 through a data-driven account free of speculative remarks. In this analysis, we will focus on the evolution of Turkey’s bilateral relations with Japan. In doing so, we will begin with a quantitative analysis of the relations to provide an overview. It should be noted that, compared to the previous cases in the project, the interaction frequency between the two countries is low. Following our quantitative analysis, we will survey the notable events between the two countries that impacted their relations vis-à-vis each other.

The Data

We use data from the publicly available Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Lab’s Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) event database in the present analysis. We discuss the methodology in Issue #1 of this series.[1] In brief, ICEWS features information on directed dyadic interactions between countries (i.e., Turkey and Japan), where each observation includes details of who (source) did what (action) to whom (target), when (time), and where (location). Each interaction is then assigned an intensity score that ranges between -10 and +10 based on the category of the interaction. Negative interaction intensity scores imply conflict, and positive interaction intensity scores indicate cooperation. We calculate monthly and annual averages of the intensity scores to form indices.

Turkey-Japan Relations: An Overview

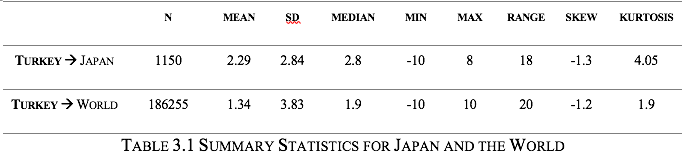

How frequently does Turkey interact with Japan, and what is the nature of its interactions? In Issue #1, we demonstrated the top interaction partners of Turkey, among which Japan is absent. The absence of Japan within the top thirty suggests that there is extensive potential for cooperation between the two countries. ICEWS features 1,155 observations with Japan between January 1st, 1995, and April 30th, 2020, of which 436 are unique interactions.[2] This number corresponds to a little over half a percent of Turkey’s total interactions of 186,255. Table 3.1 below compares the summary statistics of Turkey’s directed dyadic interaction intensity scores with Japan and the rest of the World.

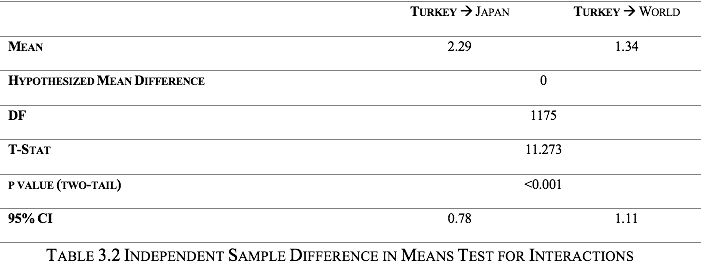

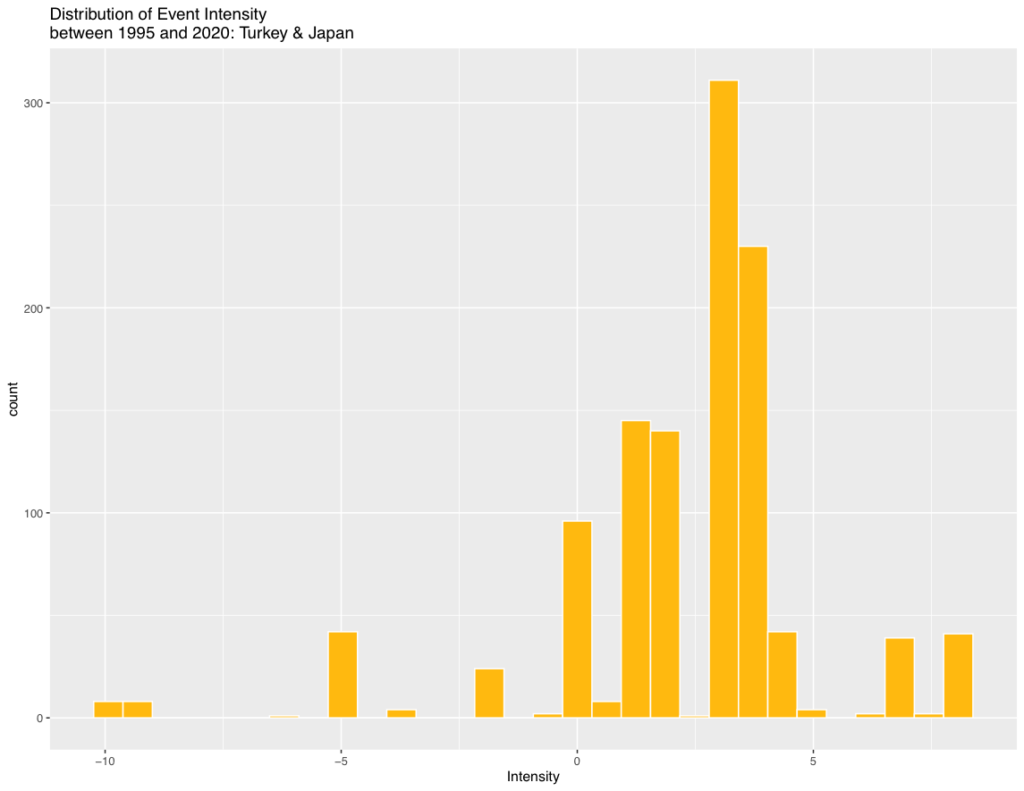

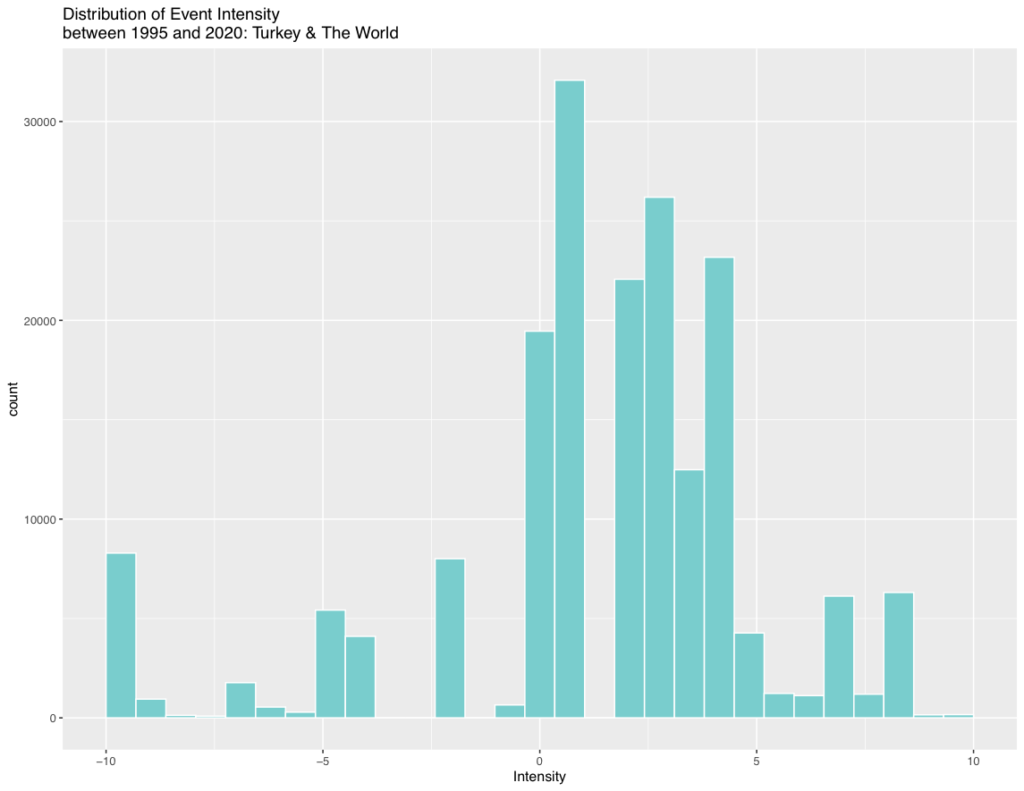

The summary statistics in Table 3.1 provides a good overview of the overall interactions’ essence. The higher average intensity score of 2.29 between Turkey and Japan compared to the 1.34 between Turkey, and the World suggests that Turkey’s relations with Japan vis-à-vis the World were, on average, more cooperative. This difference can also be qualitatively captured by exploring the shapes of the distributions. Figure 3.1 and Figure 3.2 below are event intensity score distributions. In both distributions, any value to the left of 0 suggests a conflictual interaction and to the right suggests a cooperative interaction. We also include the results of a simple difference-in-means test in Table 3.2, which indicates a statistically significant difference in the average intensity of interactions towards Japan compared to the World.

Looking at the relations between Turkey and Japan exclusively, the summary statistics from Table 3.1 suggest the instances of cooperation between the two countries were more than instances of conflict, given the median and negative skewness in the data’s distribution.

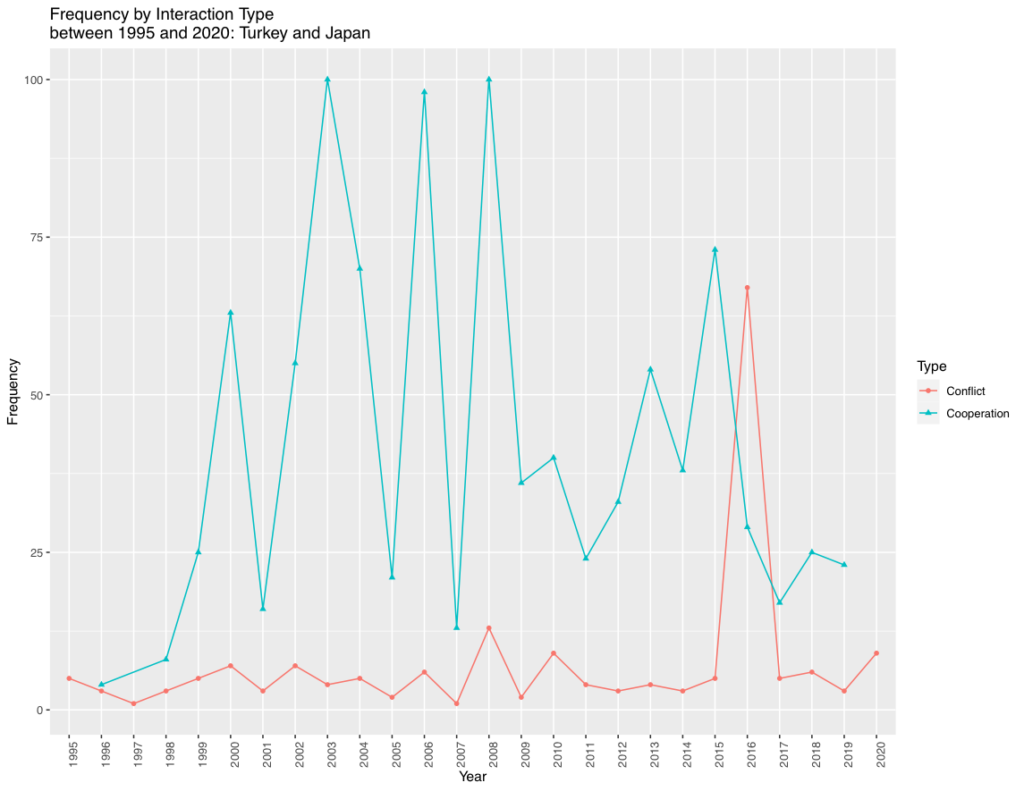

What was the variation in the frequency of bilateral interactions over time? Figure 3.3 below demonstrates the frequency of both cooperation and conflict initiations by Turkey toward Japan by year. It should be noted that this figure does not consider the magnitude of cooperation or conflict. The figure suggests the presence of a status-quo in bilateral relations: Between 1995 and 2020, interaction initiations have been overwhelmingly cooperative. There are no discernable phases of deterioration.

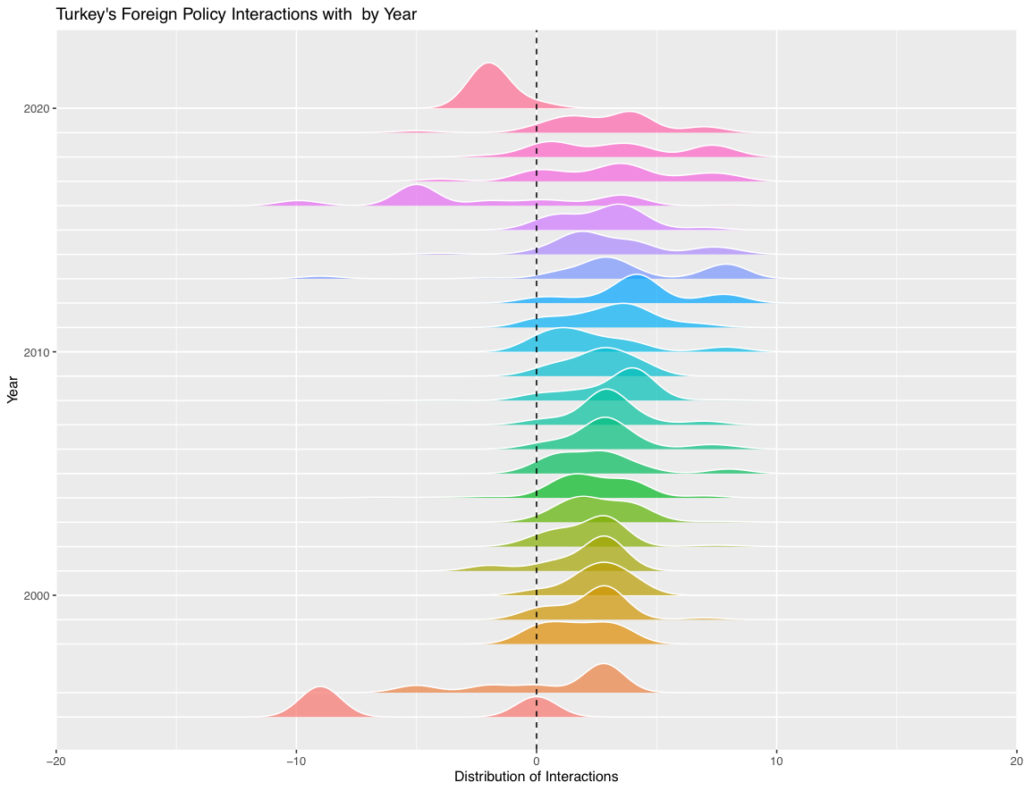

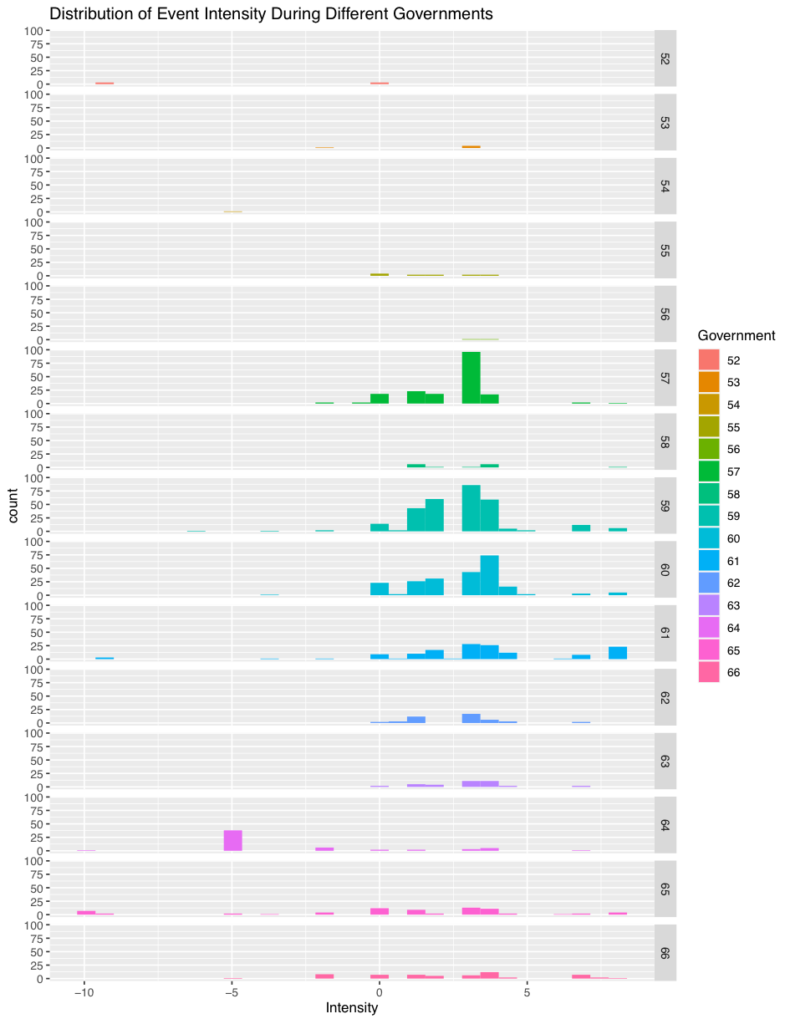

The disaggregation of interaction frequency by intensity over time provides similar information in the case of Japan and Turkey. Figure 3.4 demonstrates the annual distributions of interactions. The distribution at the bottom displays the values for 1995 and the one at the top for 2020. As always, while 0 marks neutral events, any interactions that are located to the right of 0 are classified as instances of cooperation, and to the left are instances of conflict. The magnitude of interaction intensity increases as it approaches the minimum and maximum values (10 and -10). The figure remains steady overall with the bulk of the interactions to the right of the 0 mark. Figure 3.5 demonstrates the variation in relations during a given government.[3] The intensity and frequency of interactions with Japan are at their highest during the 59th, 60th, and 61st governments.

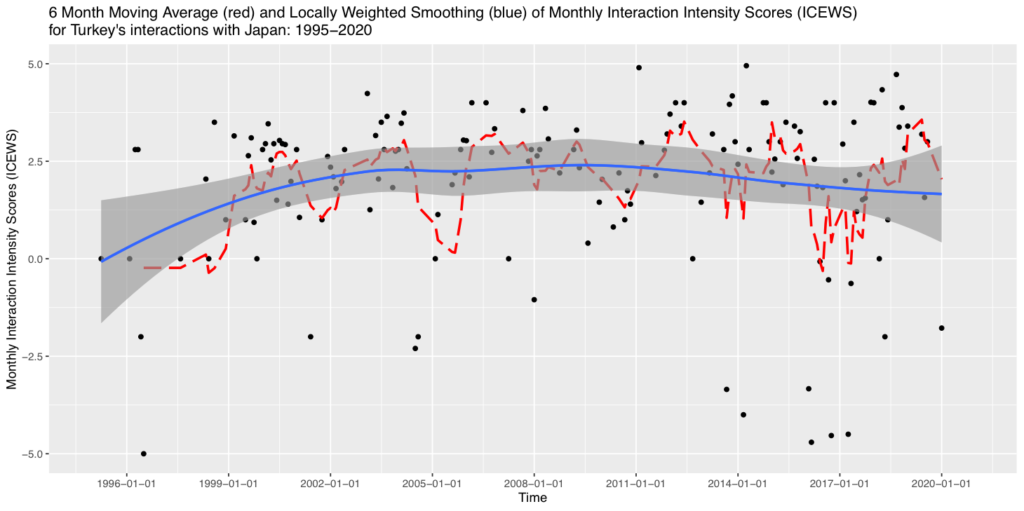

States actively react to signals that they receive from their counterparts and adjust their foreign policy towards them. An index can be particularly useful for understanding the overall evolution of the signals in bilateral relations. Our most noteworthy contribution in this report is the index of bilateral relations between Turkey and Japan, which we present in Figure 3.6.

To draw our overall dyadic relations index, we begin with calculating a simple monthly intensity average of all interactions for a given month. The values of these averages are displayed with the black dots in Figure 3.6. A dot above zero suggests that the interactions for the month were cooperative, and a dot below suggests otherwise. Note that most of the dots vary between the average intensity values of 2.5 and 5. Next, we move on to the trendlines. An upward-pointing trendline suggests an improvement in bilateral relations and an increase in cooperation, whereas a downward-pointing trendline suggests growing discord, regardless of its color. We first focus on the short-term trends and calculate a six-month moving average. This line shows the average intensity scores considering the preceding six months and is displayed with the red line in Figure 3.6. Therefore, the trendline describes the short-term cascades in which the two countries interact with each other. While occasional dips appear, there is a repeating pattern of improvement following their occurrence. Finally, we turn to the long-term and fit a non-parametric locally weighted smoothing line among all the monthly averages, which is displayed with the blue line in Figure 3.6. The grey band around the blue line shows the 95% confidence intervals. This line captures the trend in the long-term evolution of bilateral relations between Turkey and Japan. The line suggests that the essence of the relations is captured by stability.

Defining Moments in Turkey-Japan Relations

What are the momentous events that defined the relations between Turkey and Japan? In this section, we focus on the milestones that defined the two countries’ bilateral relations within the past two and a half decades. We use the ICEWS intensity variable for filtering individual milestone interactions.

Year of Turkey in Japan, April 2001

Foreign Minister Ismail Cem made an official visit to Japan. One outcome of this visit was the decision to celebrate 2003 as the Year of Turkey in Japan. [Source]

Japan’s State Minister Hashimoto visited Prime Minister Ecevit, 26 January 2001

On an official visit to Turkey, Japan’s State Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto expressed his optimistic beliefs regarding the Turkish economy. He stated that the “Turkish Economy will overcome all difficulties” during a meeting with Prime Minister Ecevit. [Source]

Japan’s Foreign Minister arrived in Turkey, 3 January 2002

Japan’s Foreign Minister Makiko Tanaka visited Turkey at the invitation of Foreign Minister Ismail Cem. [Source]

Year of Turkey in Japan, 17 February 2003

Japan declared 2003 as the Year of Turkey within the plan of promoting the historical and cultural ties between Turkey and Japan. The “Year of Turkey”, in which activities aimed at improving the commercial and economic relations between the two countries. Minister of State Ertugrul Yalcinbayir participated in the opening ceremony in Japan. Turkey’s Ambassador to Tokyo, Solmaz Unaydin, said, “We want to increase the trade balance, which is a little unfavorable to Turkey, for our country, and to increase our presence in the Japanese market.” [Source]

Cooperation for Japanese Hostages in Iraq, 13 April 2004

Prime Minister Erdogan visited Japan’s Prime Minister, Junichiro Koizumi. During the meetings, the issue of the Japanese hostage in Iraq came to the agenda of the talks. “We will cooperate on the issue of the Japanese hostage,” Erdogan said. [Source]

Emperor Akihiro of Japan hosted President Abdullah Gul, 5 June 2008

President Abdullah Gul met Emperor Akihito of Japan. During the meeting, Emperor of Japan Akihito stated that he closely follows Turkey’s Africa policies and influence on the African continent. This visit was perceived as the gateway to the celebrations of the Year of Japan in Turkey in 2010. [Source]

Year of Japan in Turkey, 3 May 2010

After President Abdullah Gul’s official visit to Japan in 2008, 2010 was declared the Year of Japan in Turkey. In the President’s opening speech at the Year of Japan reception, Abdullah Gul emphasized that the relations between the two countries must be developed in all respects where there is significant economic potential. [Source]

Nuclear Power Plant in Sinop, 25 December 2010

Energy and Natural Resources Minister Taner Yildiz signed a memorandum of understanding with the Japanese delegation in Tokyo regarding the construction of the Sinop nuclear power plant. Yildiz then met with Japan’s Prime Minister Naoto Kan, Foreign Minister Seiji Maehara, Deputy Finance Minister Mitsuru Sakurai, and Government Cabinet Secretary Yoshito Sengoku. After the meeting, Yildiz stated that Turkey wanted to work with Japan on constructing the Sinop power plant and with Russia on the Mersin power plant. [Source]

Commander of Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Forces Visited His Counterpart in Ankara, 3 February 2011

Admiral Masahiko Sugimoto, the Maritime Self Defense Forces Commander, visited his Turkish counterpart Admiral Esref Ugur Yigit to discuss the ongoing piracy problem in the Gulf of Aden between 3 and 6 February. [Source]

Memorandum of Understanding on Economic Cooperation, 19 July 2012

Turkey and Japan signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Economic Cooperation to strengthen their economic and commercial relations through the Ministries of Commerce. This agreement constituted the infrastructure of the free trade agreement between the two countries, which was planned to be made later. [Source]

Deal of Construction of Nuclear Power Plants in Sinop with Japan, 3 May 2013

Turkey signed a deal with Japan for the construction of Nuclear Power Plants in Turkey. Turkey’s Energy Ministry announced the capacity determinations for Turkish companies to assess the possible contributions of domestic energy companies to the project for the planned nuclear power plants. [Source]

Cooperation for the Defense Industry, 12 November 2013

Japanese media claimed that Turkey and Japan reached an agreement on cooperation in the defense industry and for the production of tank engines. Japan’s Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera also announced in the same week that Turkey offered different options to Japan regarding technical cooperation. [Source]

Bilateral Ties Upgraded to the Level of ‘Strategic Partnership,’ 30 October 2013

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his counterpart, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, upgraded their countries’ relations to the level of ‘Strategic Partnership’ with the signature of a joint statement. Erdogan indicated that Turkey gave exclusive rights to Japan for the construction of Sinop Nuclear Power Plant. Prime Minister Erdogan also thanked Abe for participating in opening the new train line Marmaray. [Source]

Negotiations on the Economic Partnership Agreement, 8 January 2014

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan met with Emperor Akihito of Japan in the Imperial Place. It was announced that the negotiations on the Economic Partnership Agreement started between the two countries after the bilateral meeting with Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Prime Minister Erdogan. [Source]

Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu met with Japan’s Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida, 12 April 2014

Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu met with Japan’s Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida in Hiroshima before the eighth ministerial meeting of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI). At the closed sessions, sides discussed many issues such as transparency in the field of nuclear disarmament, nuclear safety and nuclear security implementation, and establishing an area free from weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East. [Source]

Turkey Reiterated Its Will for FTA with Japan, 25 November 2014

Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan participated as the keynote speaker at the Turkey–Japan Business Forum organized as part of the 90th anniversary of Turkish-Japanese diplomatic relations. Babacan reiterated that Turkey wants to conclude the free trade agreement with Japan. [Source]

Deportation under the Foreigners and International Protection Law, 23 March 2016

In Gaziantep, a Japanese national was arrested based on the evidence suggesting that he was going to join the terrorist organization ISIS. He was deported from Turkey under the “Foreigners and International Protection Law.” [Source]

Abe Expressed His Support After the Failed Coup D’etat in Turkey, 18 July 2016

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stated that “the democratic system in Turkey should be respected” after the failed coup d’etat in Turkey. Prime Minister Abe expressed his support for Turkish society and respect for the unity and solidarity of the people of Turkey. [Source]

Prime Minister Yildirim Met with Japan’s Minister Ishii, 18 January 2017

Prime Minister Yildirim accepted the Japan’s Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Keiichi Ishii. According to the sources, the Prime Ministry stated that the relations between the two countries improved in all areas. “We will hold the necessary consultations about FETO,” Yildirim said before the meeting. [Source]

Cavusoglu’s Visit of Japan to Attract Japanese Investors, 20 June 2017

Minister Cavusoglu paid an official visit to Japan to meet his counterpart Kishida. During these meetings in Japan, Cavusoglu received Mitsubishi Electric CEO and the co-chair of the Turkey-Japan Business Council Kenichiro Yamanishi. He also met Japanese investors and businesspeople to discuss deepening Turkey–Japan economic and trade relations. [Source]

Erdogan Met Abe in New York, 21 September 2017

Before the 72nd UN General Assembly, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan received Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in New York, USA. [Source]

Abe Underlined His Support to Strategic Partnership with Turkey, 4 April 2018

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Japan received Deputy Prime Minister Recep Akdag in Tokyo. Abe underlined Japan’s desire to deepen its strategic partnership with Turkey. Akdag said, “We want to increase the cooperation in the fight against natural disasters with a 5-year joint action plan with the communication over the relevant ministers from the two countries.” [Source]

Erdogan and His Executive Team Met Abe in New York, 25 September 2018

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan met Prime Minister Abe of Japan in New York, where he attended the 73rd UN General Assembly. Minister of Foreign Affairs Mevlut Cavusoglu, Minister of National Defense Hulusi Akar, Minister of Health Fahrettin Koca, and Minister of Industry and Technology Mustafa Varank also attended the meeting. [Source]

Year of Turkey in Japan, 19 March, 2019

The year of 2019 was declared the Year of Turkey in Japan with a reception attended by Japan’s Princess Akiko and Turkey’s Minister of Tourism and Culture Mehmet Nuri Ersoy. [Source]

Japan Criticizes Turkey’s Syria Operation, 10 October 2019

Following Turkey’s operation into the Northeastern Syrian border, Japan’s foreign minister, Toshimitsu Motegi, said: “Japan is deeply concerned that the latest military operation would make the settlement of the Syrian crisis more difficult and cause further deterioration of the humanitarian situation. Japan once again underscores its position that the Syrian crisis cannot be solved by any military means.” [Source]

[iheu_ultimate_oxi id=”23″]

[1] Lautenschlager, Jennifer, Steve Shellman, and Michael Ward. 2015. “ICEWS Event Aggregations.” Harvard Dataverse V3.

[2] Notable events are captured by multiple news agencies leading to repetitions in the dataset.

[3] There are fifteen governments in our timeframe. The terms of these governments are as follows: the 52th Government of Turkey, October 30th, 1995, to March 6th, 1996; the 53th Government of Turkey, March 6th, 1996, to June 28th, 1996; the 54th Government of Turkey, June 28th, 1996, to June 30th, 1997; the 55th Government of Turkey, June 30th, 1997, to January 11th, 1999; the 56th Government of Turkey, January 11th, 1999, to May 28th, 1999; the 57th Government of Turkey, May 28th, 1999, to November 18th, 2002; the 58th Government of Turkey, November 19th, 2002, to March 12th, 2003; the 59th Government of Turkey, March 14th, 2003, to August 29th, 2007; the 60th Government of Turkey, August 29th, 2007, to July 6th, 2011; the 61th Government of Turkey, July 6th, 2011, to August 29th, 2014; the 62th Government of Turkey, August 29th, 2014, to August 28th, 2015; the 63th Government of Turkey, August 28th, 2015, to November 24th, 2015; the 64th Government of Turkey, November 24th, 2015, to May 24th, 2016; the 65th Government of Turkey, May 24th, 2016, to July 9th, 2018; the 66th Government of Turkey, July 10th, 2018 which is ongoing. We include the data for the 51st Government as part of the 52nd Government given its short term.

- This article has been published in cooperation with Friedrich Naumann Foundation.

Photo: Colton Jones